The first German World Championship race on the Solitude

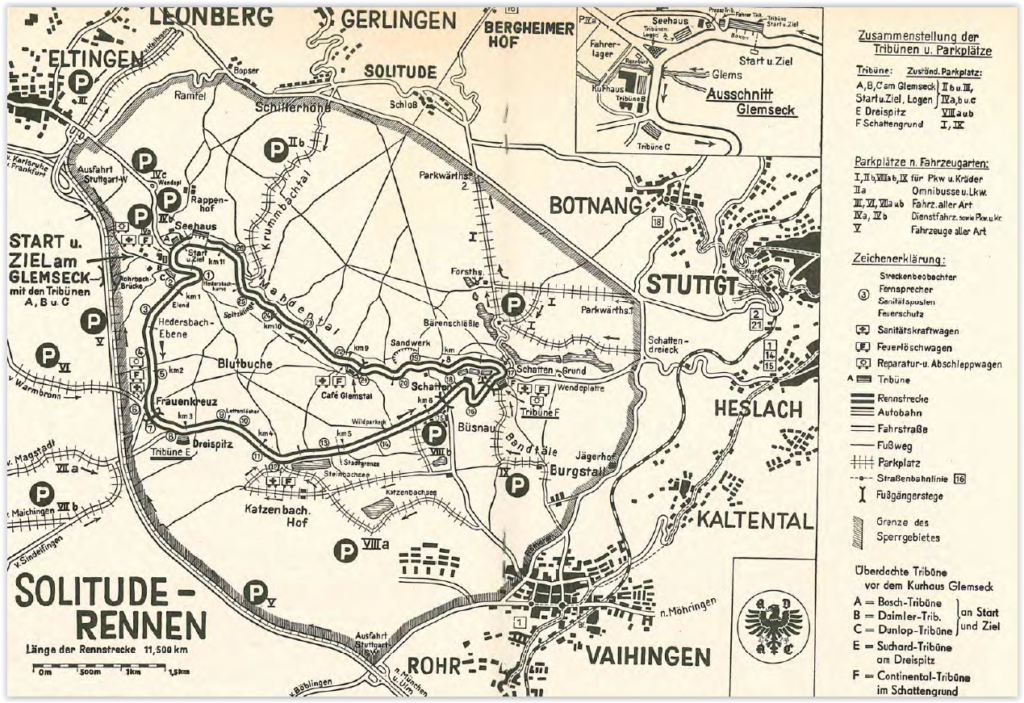

The expectations of the fans, teams and pilots from Germany before this premiere were certainly low, but thanks to many fast drivers, their hopes were still very high. Many secretly hoped that there would be cause for celebration. The Solitude race track near Stuttgart had a lot to offer and the backdrop of the 11,453 km long course was absolutely magnificent and worthy of the World Cup. It had already emerged in advance that DKW and NSU in particular had done their homework and, despite having very modest resources shortly after the war, had put a lot of effort into preparing for this event. After all, over 400,000 spectators are said to have made a pilgrimage to the track to see their compatriots compete against the top international stars. It’s hard to imagine that even one person would have regretted coming. German pilots scored World Cup points in all classes and two of them became known nationwide, at least among sports fans, on July 20, 1952.

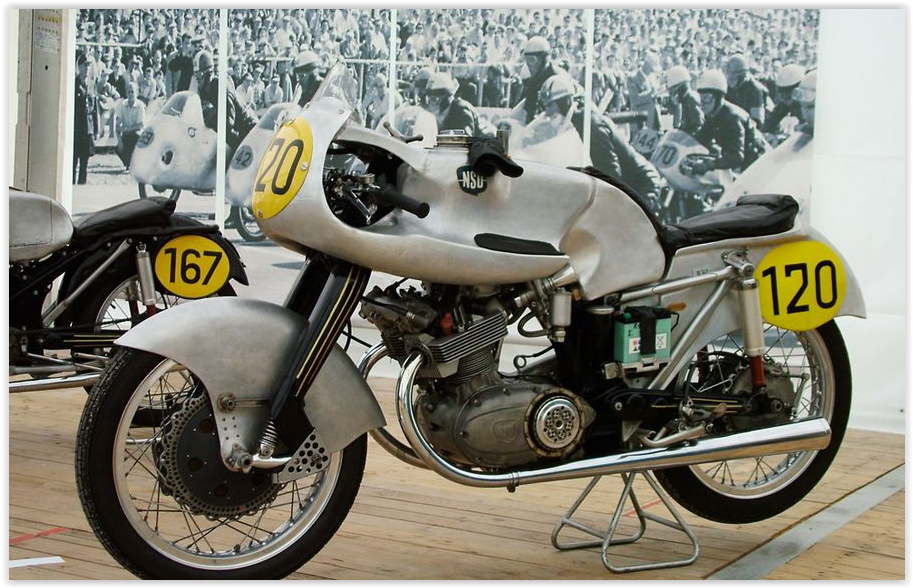

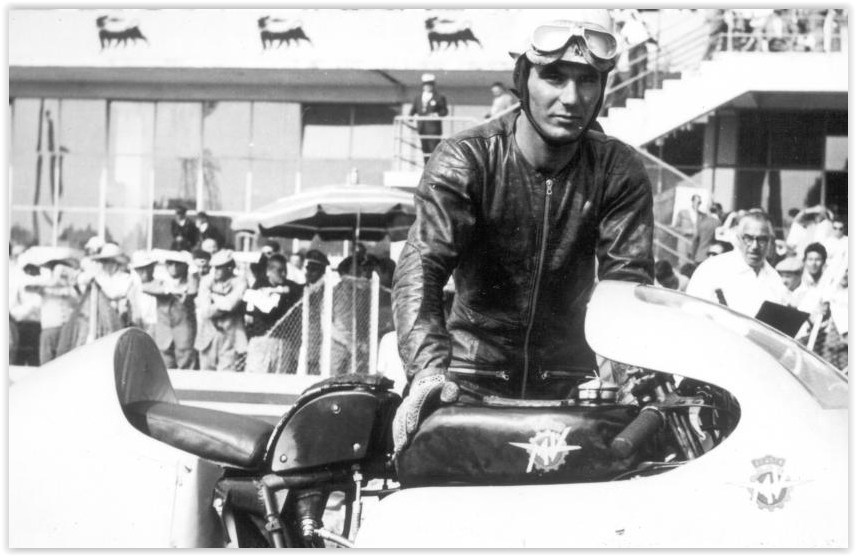

The 125cc race – a meteoric career began

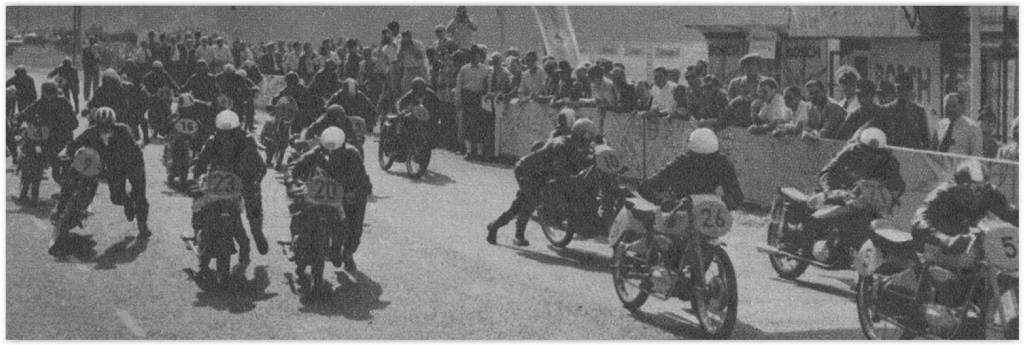

In the eighth liter class, the German pilots were merely outsiders and were considered, even by experts, to have absolutely no chance against the many established factory drivers from abroad. Above all, NSU had already lost its most important figureheads before the start due to the training accidents in Hoffmann and Colombo. But after the start with Werner Haas, a rebellious young pilot suddenly defended himself against the two world championship leaders, Ubbiali and Sandford. As an NSU substitute driver, the young man from Augsburg simply refused to let himself be left behind by the two top stars and fought against them with a knife between his teeth. In the end, after 10 laps, he crossed the checkered flag just ahead of the reigning world champion from Italy, while world championship leader Sandford had to settle for third place, almost 14 seconds behind. With 5th place behind the Italian Angelo Copeta (like Sandford on MV Agusta), Herbert Luttenberger managed to underline the top result for NSU in their home race. This marked the beginning of an almost unbelievable development for the career of Haas, who was only 22 years old.

An incredible performance was followed by the next sensation

Of course, the audience was already completely over the moon after Haas’ victory, but things were to get even better for the countless fans and their heroes. But this time it wasn’t NSU, although the Englishman Bill Lomas was absolutely equal to the Moto-Guzzi pilot with his Rennmax in the 250 cc race before a connecting rod bearing failure threw him out of the race. But local hero Rudi Felgenheier stepped into the breach for DKW. He benefited from a collision between the two fighting cocks Ruffo and Lorenzetti, who were already clearly in the lead on their factory Moto-Guzzi. On the penultimate lap, the latter slipped while attempting to overtake, causing his teammate to fall, who suffered a double fracture of his lower leg and arm injuries. Enrico Lorenzetti, on the other hand, remained uninjured and Lomas, who had previously been in P3, broke down shortly afterwards with engine failure. Bill Lomas had been loaned out to NSU from AJS after the accidents involving the two regular drivers and without this bad luck he would probably have taken the second victory of the day for the factory from Neckarsulm in Swabia. The season was over for Bruno Ruffo and, like Geoff Duke after his accident at the Schottenring, he did not return to the race tracks in 1952.

The double premiere after the competitors’ bad luck

In front of four of his compatriots, after the bad luck of his competitor Rudolf “Rudi” Felgenheier, he achieved a sensational victory with a lead of over 50 seconds over second-placed Thorn-Prikker on his private Guzzi. Hermann Gablenz saved the honor for Horex with third place on the podium, followed by veteran Ewald Kluge on the second-best factory DKW and Gehring on another Moto-Guzzi. Only his brand colleague Wheeler was the only foreigner to score one last World Cup point with 6th place. Behind Bruno Böhrer (Parilla), two Austrians, Mayer and the young Hollaus, saw the checkered flag, and the latter was soon to make a name for himself. For DKW it was the first victory in the World Championship after several European Championship titles before the war. In the 1930s, this brand dominated the middle categories, thanks in particular to Ewald Kluge, the winner of the 250cc TT in 1938 and two-time European champion of the 250cc class in 1938 and 1939. The old master also won his first world championships. points after finishing 4th on Solitude. But the most remarkable fact was ultimately the first GP victory for a two-stroke engine.

After a sensational start, further notable successes

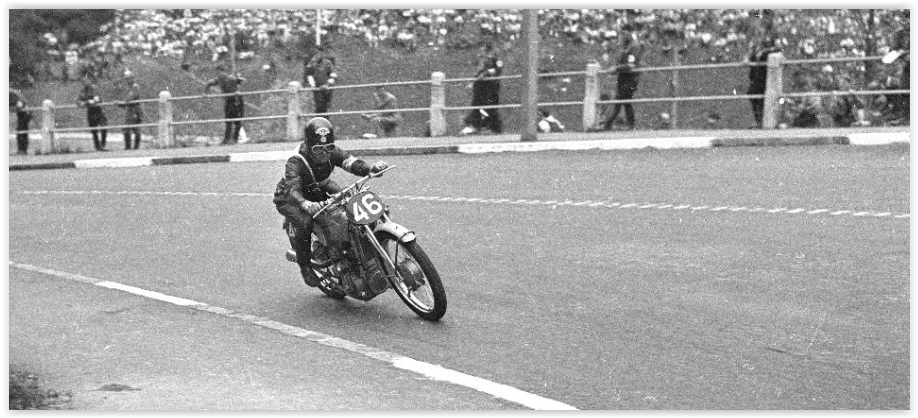

There was nothing short of a mass disaster in the final world championship race for the 500cc machines. Of the 26 drivers who started, only 11 finished the race, which covered the huge distance of 207.0 km after 18 laps. With Reginald Armstrong, an Irishman for Norton won both races in the two largest categories up to 350 and 500cc on the difficult course west of Stuttgart. However, in both cases his victory was extremely close, if not questionable. With Ken Kavanagh it was an Australian who crossed the finish line just a blink of an eye after his teammate and the media immediately talked about a clear stable order. In the premier class, Syd Lawton completed the podium for Norton, while his English compatriot Bill Lomas (AJS) snatched this place from him in the category up to 350cc before the checkered flag. Behind him, Ewald Kluge scored the first two World Championship points in this class for DKW, followed by Ernie Ring. While BMW was missing from the factory due to what they said was an immature motorcycle, Hans Baltisberger rode his private 500cc BMW to an excellent sixth place behind Leslie Graham (MV Agusta) and thus scored his first World Championship point.

The high number of local unlucky people at the first German GP

It wasn’t just Ruffo, Lorenzetti (this one was more of his own fault) and Lomas, along with the riders who had already had serious falls in training, who were out of luck; the list of unlucky people was much longer at the premiere on the Solitude. Old master H. P. Müller, as the best in training, had annoying misfortune this time in the 125cc race when, after initially leading in P3, he stopped lying on his private FB-Mondial with engine damage. Things got even worse in the same race for Otto Daiker, who fell badly after a few kilometers and had to be taken to hospital with a fractured skull, but luckily he survived and later returned to the racetrack. In the 250s, Siegfried Wunsch (DKW), who traveled from Ingolstadt in Bavaria, had the bad luck of being stranded on the first lap with an engine failure. In the 350cc category, despite losing his left footrest, he was in 6th place for a long time until he was eliminated due to a harmless fall. Karl Hofmann fell during training, just like world speed record holder Hermann-Böhm, who had a dangerous-looking fall in the Glemseck curve during the final training session on Saturday, but escaped with minor bruises. BMW driver Groß from Bad Windsheim (BMW) also crashed in the 500cc race, while Friedel Schön (Horex) had the annoying misfortune of being in fifth place and having to give up three laps before the end due to an engine defect.

The conclusion after the German Grand Prix

It only now became clear to most observers from home and abroad that the history of the two-wheel Grand Prix should have been rewritten with German participation in the years 1949 – 1951. It was and will always be up to each individual to decide what sense the banishment of German athletes should make at this time. Germany was in ruins and fascism was in ruins anyway, just as dictatorships existed and will continue to exist in many other countries. Stalinism, like Nazi rule, led to millions of victims and Italy’s Mussolini, along with many other state leaders of that time and later, was nothing other than a criminal. Nevertheless, the Italians were allowed to take part and share the victories and titles together with the English in the first three years of the World Cup. No matter, motorsport history from 1952 onwards was intended to prove what pilots and teams from West and East Germany were capable of. The weekend at Solitude was something like the initial spark for this.

Unless otherwise stated, this applies to all images (© MotoGP).

No Comments Yet