The second quarter of the season with the Tourist Trophy

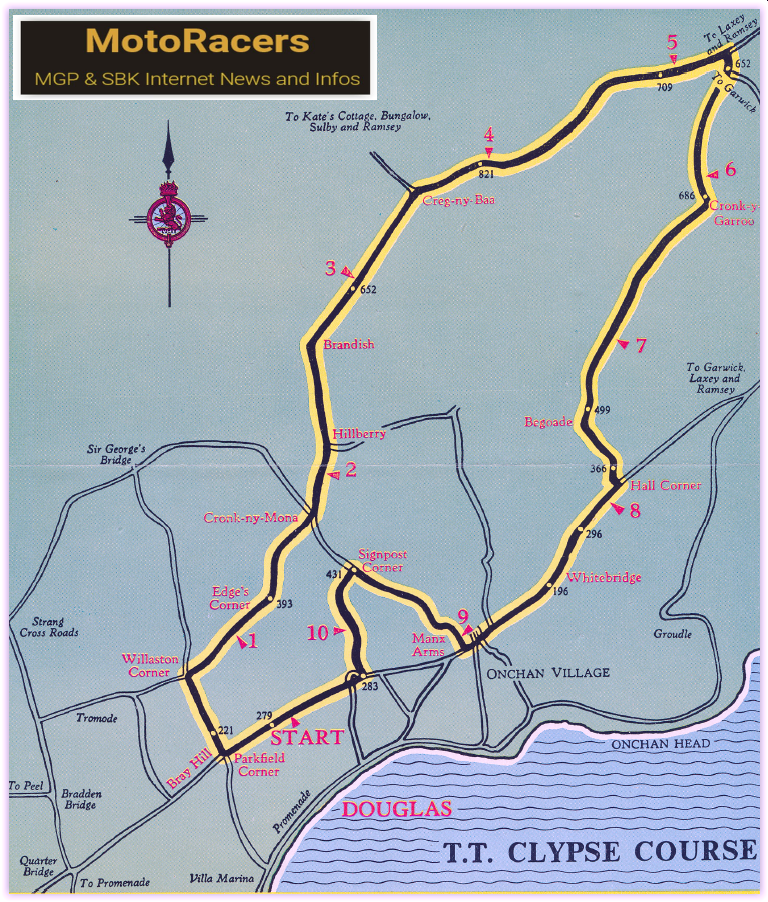

After the French Grand Prix on one of the most boring tracks on the calendar in terms of its layout, along with the A1-Ring in Austria (later the Red Bull Ring), this time things really got down to business on the Isle of Man. The larger two classes up to 350 and 500 cc (called Junior and Senior) were raced on the Snaefell Circuit, while the smaller two categories (lightweight up to 250 cc and ultra-lightweight for the 125cc) were raced on the much shorter Clypse Course the event came. The specialty was that some places such as the famous Governors Bridge were driven in both cases. The shorter course only came into play in the World Championship from 1954 and at that time only for the smallest category and the sidecars. The 250s were now also able to enjoy the shortened route. The shorter route is named after a water reservoir or rather a small reservoir called Clypse. In the end, however, the British hosts were more concerned about the issue of route choice than the fact that, for the first time in history, not a single English manufacturer remained victorious. It is also important to mention that a total of 77 falls occurred during training alone.

Lots of innovations and the birth of a new superstar

As usual, the traditionalists had trouble with it and on the other hand, a course length of two or more laps was quite sufficient for the smaller categories. Conversely, 7 laps on the Snaefell Circuit with a length of 424,952 kilometers were basically complete nonsense for sprint races or even a world championship. In 1955, however, this did not seem to bother most of those responsible and the FIM had already been publicly denied any competence in technical and sporting issues for a long time. But back to the sporting events. On the weekend of the Tourist Trophy, an event shook the sporting world that could hardly be surpassed in terms of drama. To get to the point, an out-of-control racing car became a deadly missile at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, claiming the lives of 83 people. Almost at the same time, on the Isle of Man, a man was supposed to achieve something at the TT that was unimaginable back then and still sounds incredible today. This is especially true in the third millennium, in which starts in several categories are already a thing of history. But let the following paragraphs tell what William A., known as Bill Lomas, achieved this season.

The ultra-lightweight class up to 125cc

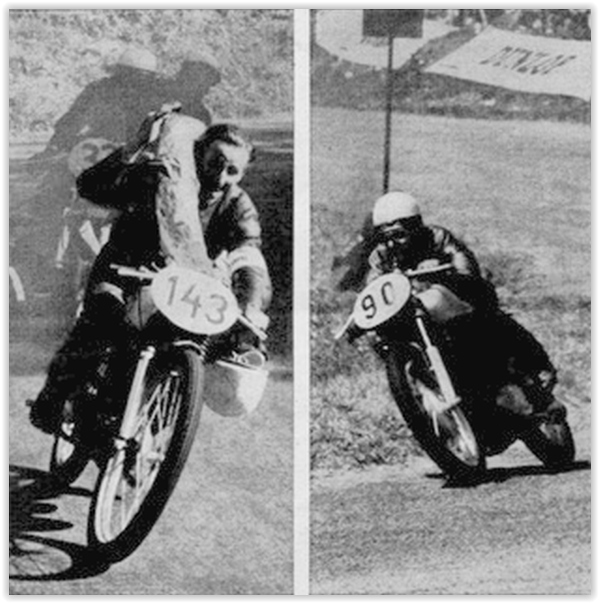

The previously mentioned racing driver was no stranger to the scene from 1950 onwards, as he had already finished seventh in the final standings in the World Championship up to 350cc on Velocette that season. With the exception of 1954, he had scored World Championship points every year since then and now his hour had come on the Isle of Man. The fact that he won in the ultra-lightweight class up to 125cc with MV Agusta on an Italian brand was not a problem for the British audience. Since this category was introduced in 1951, only pilots with motorcycles from the country with the shape of a boot have won. Without the NSU pilots, who had dominated in previous years, there was a duel between MV and FB-Mondial. As in Reims, Carlo Ubbiali won ahead of Luigi Taveri (both MV Agusta) and Giuseppe Lattanzi on the fastest Mondial. Behind him as the best Englishman was Bill Lomas, ahead of Webster and Porter (all MV), as well as two other compatriots. Ubbiali was now tied with the Swiss (with 20 points each) in the lead in the interim rankings, followed by Lattanzi as one of the pilots who did not survive the season with 11 points. Lomas missed the podium in fourth place, but the Englishman had only completed one of four races. Ubbiali, on the other hand, was very happy about his first TT triumph after numerous failed attempts.

The second race of the season for the 250cc class

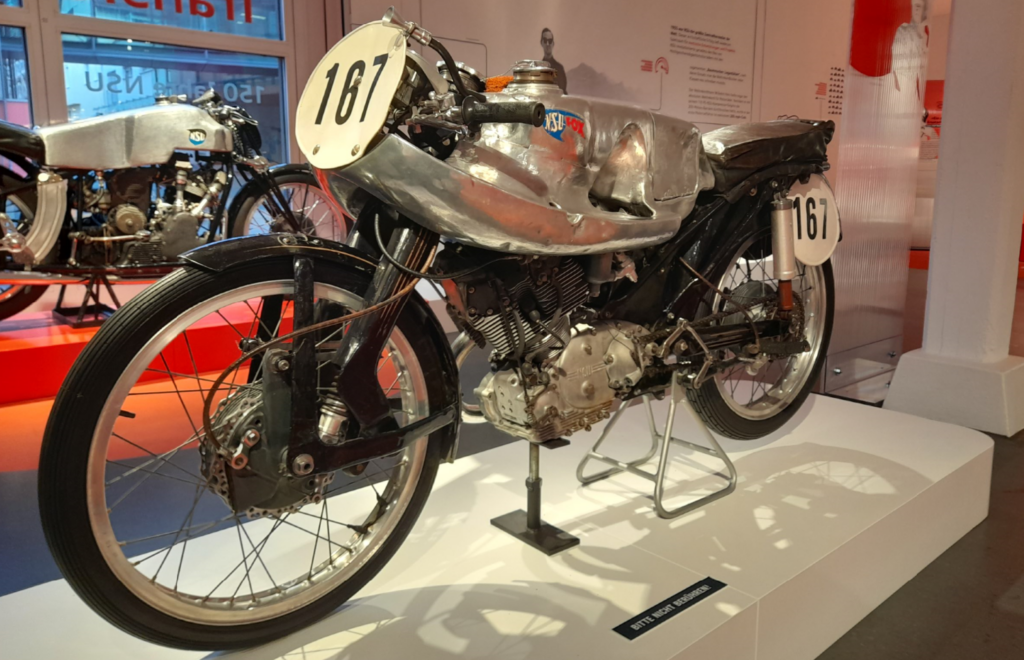

In addition to the smallest class, the race up to 250cc and that of the teams also took place on the smaller Clypse Course, which was described as a shame by many observers at the time. There were only 16 pilots at the start in the lightweight class. For the first time, MV Agusta also took part as the only factory team with a single-cylinder engine bored out to 175cc. German Veteran H.P. Müller for this reason, on the NSU Sportmax had little chance of placing at the top. But as is often the case, races write their own stories. Like the many pilots on the English makes and various Moto-Guzzis, Müller was once again in the status of a private rider. In contrast to the two Irishmen Spence and Wright on the at least outwardly identical NSU, the German stayed seated and managed without a fall, although a long way behind the winner Lomas (with the new MV) and the second-placed Sandford on his two-year-old, former factory -Guzzi, crossed the finish line with 3rd place, well above expectations. Two of the factory MVs did not see the checkered flag. After a bad start, Taveri, like his MV factory colleague Masetti, who was still in P4 on the second lap, retired during the race.

The junior category up to 350cc

Similar to how Werner Haas became a works driver virtually overnight on the Solitude in 1952 because the two regular drivers were injured at the same time, Bill Lomas also joined a works Guzzi on the TT. He had moved up to the Italian team in place of his compatriot Dickie Dale, who was injured in a car accident. And just like the Irishman Reg Armstrong in 1953 at the Ulster GP as an NSU newcomer to the 250cc, Lomas thanked him straight away with a sensationally strong performance. Of course, he benefited from a top speed advantage of around 20 km/h over the English competition from AJS and Norton, which made things much easier for Bill. Cecil Sandford also arrived two places behind him as winner in the single-cylinder Guzzi. The only astonishing thing was that the Scot Mc Intyre saw the checkered flag on his private Norton in front of him and the three factory Nortons from Surtees, Quincey and Hartle behind him, thus embarrassing the factory team of the English who had previously dominated the larger classes. At the finish, Mc Intyre even stated that he had to slow down because his brakes overheated and that otherwise he might even have won. The performance of Sonnyboy W.A. However, this shouldn’t detract from “Bill” Lomas’s double victory at the TT.

The premier class of Senior TT up to 500cc

Geoff Duke was definitely at the peak of his career when he competed in his home country with already five titles (two in the 350cc and three in the 500cc). As the reigning world champion, he was the heavy favorite for the Senior TT, as he had already achieved five victories on the Isle of Man. The number six meant a special size for him in terms of Tourist Trophy victories and number of World Championship titles in 1955. In ideal conditions this time, in addition to the English, there were also 6 pilots from New Zealand, 5 Australians, 4 South Africans, 2 each from Swedes, Finns and from Ceylon (now Thailand), as well as a rider who had traveled from France. With a new record lap, Duke made it clear early on that victory could only come through him. With Carter (Matchless, due to a valve failure), Karlsson (Norton, with carburettor problems), Matchless pilot Murphy and the fallen Tait (Norton), as well as a few others, there were, as expected, many retirements. Ultimately, however, this didn’t matter for the superior triumphant Geoff Duke on his 4-cylinder Gilera, as he saw the checkered flag almost two minutes ahead of his factory team colleague Armstrong. Kavanagh brought the fastest Guzzi home in P3 and completed the podium ahead of Brett and Mc Intyre on the best Nortons and Derek Emmett on his Matchless.

World championship premiere for round 4 on the Nordschleife

The traditional route of the famous Nürburgring in the Eifel was already famous far beyond the borders before the war and was as notorious as the Isle of Man. After the Solitude near Stuttgart and a failed interlude at the Schottenring in 1953, the Nordschleife of the Nürburgring came to the fore for the German Grand Prix. After the Tourist Trophy it was the turn of another course with a great history, which usually provided a spectacle. But one circumstance ensured that, in contrast to the previous three years, there was hardly any interest from the local media. Things also suddenly looked bleak in terms of spectator numbers, as only around 30,000 visitors came to the Eifel. Only one year ago, over 400,000 more spectators made the pilgrimage to Solitude. In 1955 there were also voices that blamed the annual changing venues since 1952. At that time, two institutions, ADAC and DMV, were also competing for supremacy in two-wheel racing. As a result, several events fought over the holding of the German GP. But in reality, the media at that time were at least partially to blame for the decline in audience and decreased interest because they only reported sparingly about it from 1955 onwards. The resignation of Werner Haas as three-time world champion and the NSU withdrawal from Grand Prix racing naturally contributed to this.

The fourth 125cc German Grand Prix

Of course, in the absence of the withdrawn NSU factory team MV Agusta was the clear favorite and the private drivers equipped with these fast four-stroke single-cylinder engines also had a good chance of scoring points. A small group from East Germany, the former GDR, was hardly noticed when they got their IFA single-cylinder two-stroke engines ready to race. The former DKW halls in Zschopau were of course produced for the Wehrmacht during the Second World War and therefore after heavy bombing raids only one of them was left that was halfway usable. The IFA was now produced on the basis of the DKW RT 125 from the 1930s and for several years it has also served the people from Saxony as a basis for racing. Although they lacked many things that were taken for granted in the West. For example, aluminum was extremely difficult to find in the GDR, as were good spark plugs or useful tools. That’s why they often even received help in the paddock from their Western colleagues. And suddenly they were there and old master Bernhard Petruschke, known as “Petrus”, and his teammate Erhart Krumpholz drove into the points to everyone’s surprise. However, this was just the beginning of a difficult story. The works MV under Ubbiali, Taveri and Venturi won, followed by private driver Karl Lottes from West Germany. Everyone else had to bow to the friendly little delegation from the GDR.

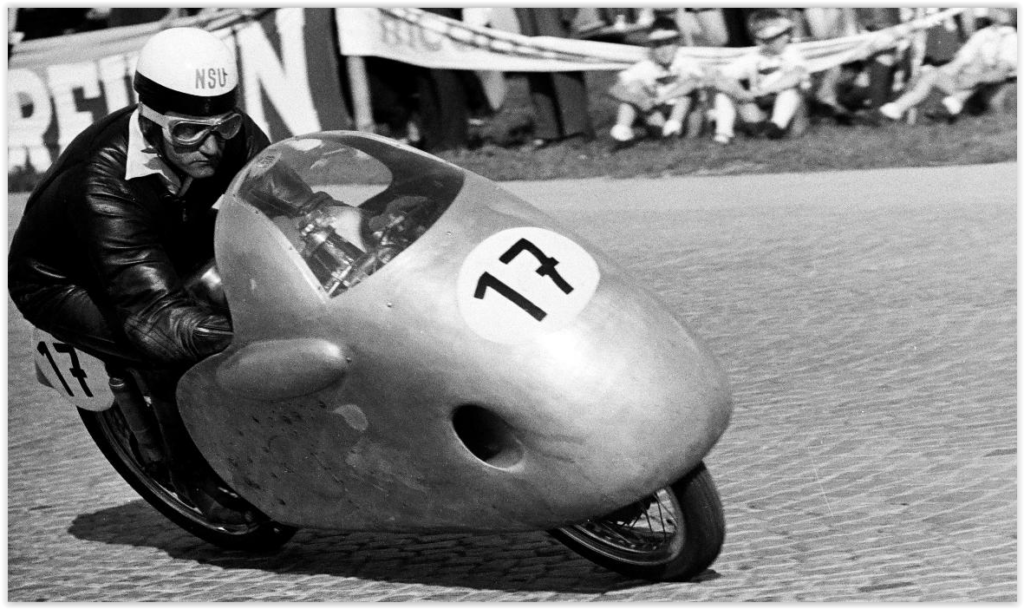

The masterpiece of the veteran in the quarter liter class

The almost unbelievable success story of H.P. (often simply called “HaPe”) Müller, we dedicated a separate chapter to on our site (see “History – Riders”). The Bielefeld rider already won before the war on a DKW in the European Championship and in car races on an Auto-Union with over 500 hp Racing car. In addition, a year after his highlight, when he won this race at the home Grand Prix at the age of 45, he would also set several world speed records for NSU. Before that, as an NSU works rider, he was clearly in the shadow of the works riders Haas and Hollaus confessed, when the crowning of his long career followed in the status of private rider on the NSU. He irresistibly pulled away from the rest of the field and even the factory MV Agusta’s, which now had just over 200cc, had to admit defeat, with Taveri the only one who came in 4th behind Brand (NSU) and Sandford (Guzzi). Initially, Lomas had fought for the lead with Müller before he retired with technical problems on his factory MV. After only two of this time only five rounds of the 250cc World Championship, the German was in the lead with 12 points in the intermediate rankings. Behind them Sandford with 10 points ahead of Lomas (8), Brand (6) and Guzzi private rider Wheeler with five.

The repeat offender from England hit again up to 350cc

In contrast to the smaller two categories with MV as the only participating factory team, in the 350s there was at least a duel between Moto-Guzzi and DKW. So the Italians Bill Lomas, Duilio Agostini and Ken Kavanagh were at the start, while “Gustl” Hobl, “Sissi” Wünsche, Karl Hofmann and trial driver Bodmer tried to hold up the flag for DKW. Masetti and Bandirola also appeared, so let’s call it a semi-official MV to be on the safe side. After the start, it was August Hobl who took the lead and, pursued by Surtees and Lomas, tried to stay ahead through the demanding parts of the Nordschleife, which is over 20 kilometers long. But just one lap later, Lomas took the lead on his Guzzi, with the German following him in sight all the way to the finish. Behind him, Surtees didn’t give up either, and he always stayed close to Hobl, but was unable to overtake him. In the end it stayed in this order and with Cecil Sandford and Ken Kavanagh (both Guzzi) ahead of the second best DKW from Hofmann, the points were awarded. Since only two out of six rounds in the World Championship had been completed with up to 350cc, Lomas’ lead over his pursuers in the interim ranking after the German GP was of minor importance.

Next favorite win in the premier class

With Gilera against MV Agusta there was now only a duel for victory, after the competition with one- and two-cylinder engines had absolutely no chance, even on road courses. BMW, AJS and Norton had obviously resigned themselves to this. At that time, these manufacturers also lacked the funds for expensive new developments, also because cars were gaining ground in terms of sales figures compared to motorcycles. MV Agusta was in a special position in this regard as a producer of helicopters and Gilera had a long tradition with 4-cylinder engines. They were the benchmark in racing, especially after the Second World War, and that’s why Geoff Duke switched to the Italians in good time. As the undisputed strongest driver of his time, he also proved his special class at the Nürburgring and only BMW works driver Zeller, as an expert on the Nordschleife, was able to stay halfway on his heels. The two Italians Bandirola and Masetti on their MV reached the finish line, over 3 minutes behind the two leaders. Colnago (Gilera), who was still suffering from a previous crash, only finished fifth ahead of Ahearn on the fastest Norton. Armstrong, who had previously been the leader ahead of Duke in the intermediate classification, stopped in round 4, meaning that Duke took the lead just ahead of him at the halfway point of the season. This with 24 points compared to 18 for the Irishman and Bandirola with 10, all other competitors were already far behind.

A tragic fate overshadowed the Eifel premiere

Unfortunately, there was one victim at the German Grand Prix on the extremely dangerous Nordschleife, surprisingly unlike the TT. After the Argentinian Ricardo Calvagni had a fatal fall in the Fuchsröhre, he died at the scene of the accident. His compatriot Armando Poggi set a horrendous pace immediately after the start. However, this was his downfall shortly afterwards at the Aremberg curve. He took the curve too quickly, fell and, among other things, broke both arms. Calvagni, who was following him, was able to pass the scene of the accident and continued driving. In the meantime, an ambulance rushed to the scene of the accident. On the second lap, Calvagni was surprised to see the ambulance on the race track and he drove straight ahead without braking and fell down the embankment at Fuchsröhre. With a broken neck, Ricardo had no chance of survival.

A World Championship in crisis

Disappointingly, FB-Mondial did not compete at the Nürburgring, meaning they voluntarily gave up the fight for the title against MV Agusta. After the factory withdrawal of NSU and the English factories of AJS and Norton, the motorcycle world championship was now finally in a deep crisis. BMW had only participated half-heartedly since 1952 and the DKW brand, which was so successful before the war, had to struggle with stability problems with its three-cylinder two-stroke engines. Horex and Adler also withdrew after 1954. Racing in general was increasingly scrutinized by the public after the tragedy at Le Mans, and the far too many deaths on two-wheelers over the years naturally contributed to this. Criticism of the FIM also grew in the media of many countries, including England, Germany and France. Because this institution, which is the highest motorsport authority responsible for the well-being of racing, mostly just watched instead of reacting, works were repeatedly released that, in the eyes of many observers, could have been kept. But for decades, those in charge of the FIM continued to only react when it was too late and appeared to rule autocratically, as if they were only interested in their own well-being and their power. At least that is the echo of many observers across several eras of motorsport, including countless journalists and experts.

Unless otherwise stated, this applies to all images (© MotoGP).

No Comments Yet