Shrunken minimal edition with sparse participation

Except for the drastically reduced number of manufacturers compared to the first from 1949 and the mid-1950s, one felt like one had been transported back to the early years of the motorcycle world championship. Mainly because the German factories and drivers were not allowed to take part in the first three years. This was for purely political reasons, mind you, although the Soviet Union, Japan and other countries were also guilty of the most serious war crimes and politicians like Mussolini and the Spanish dictator Franco were hardly any better. From 1952 the German pilots and factories were admitted and within a very short time NSU and NSU dominated the smaller two classes almost at will from the following year. After the tragic death of Rupert Hollaus in an accident in Monza in 1954, the Neckarsulm factory unfortunately withdrew again and two years later DKW also withdrew for purely economic reasons. Fortunately, BMW had returned to the decision it had made before the 1956 season finale in Monza to withdraw from the Motorcycle World Championship as a factory. At least with their reigning vice world champion Walter Zeller they continued to take part as a one-man team. In any case, we are of the opinion that a real World Cup only took place from 1952, when the best nation from the last few years before the Second World War was eligible to take part again. We have listed arguments for this attitude in the following article, although everyone should of course form their own opinion:

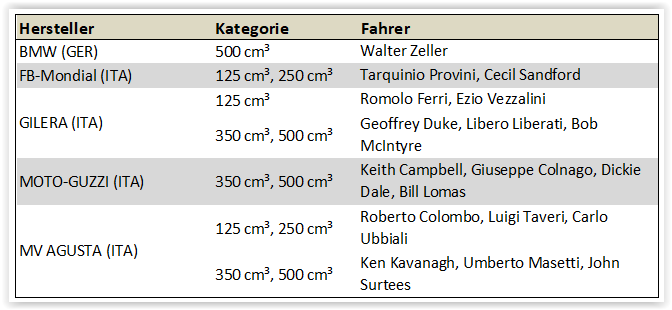

Drastic shrinkage of factory participation by all nations

In countries like Germany and England, car sales rose rapidly and the days when motorcycles were the poor man’s means of transportation were increasingly becoming a thing of the past. Traditional brands such as Adler, Benelli, DKW, Excelsior (these only before the war), Horex, Moto Morini, NSU, Matchless, Velocette and now also AJS and Norton had disappeared and had now withdrawn from international motorcycle road racing. The French were never really involved, at least as far as the manufacturers were concerned, countless of which would soon disappear from the scene over the years, as in other countries. Now, for the first time, no English manufacturers were there anymore. Our composition of the factory teams underlines how much the golden 50s of motorcycle racing were already a thing of history in 1957. There were fewer than ever before and at that time there was unfortunately no end in sight to this drastic shrinking from at least 8 to now only 5. To make matters worse, on April 21, 1957, crowd favorite Bill Lomas and Geoff Duke crashed in the 350 cc race at Imola, meaning that the two of them (Duke for the second time after the previous year) missed the start of the season.

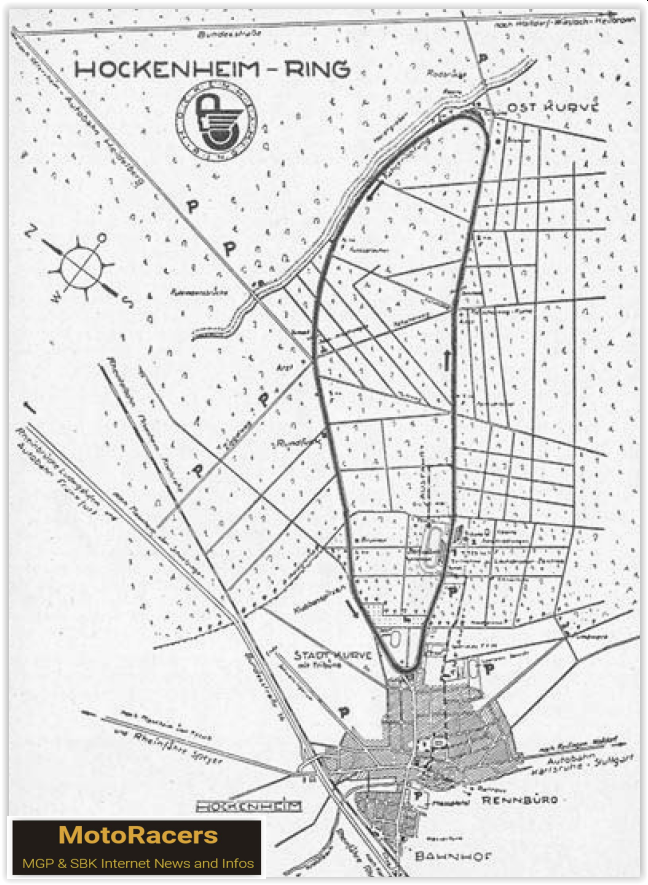

Season opener in Germany with the premiere for the Hockenheimring

It was of course a great shame for the organizer that two years after NSU, at the end of the previous year DKW, one of the most competitive brands in the smaller and medium-sized classes, had unfortunately withdrawn from the factory. Nevertheless, at least in the smallest category, a German should surprise with a sensational result, even if not everyone was completely enthusiastic about it in these strange times. The racetrack, located in Baden and thus the southwestern part of Germany, cannot be described as particularly demanding given the layout at the time, although this was not unusual at the time. At that time, Monza only had 7 corners, two of which could be described as left-hand bends. At a time when factories were almost constantly trying to outdo each other with new world speed records, racing was particularly focused on top speed. However, on road courses such as the TT on the Isle of Man, Dundrod near Belfast in Northern Ireland, Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium and the Solitude near Stuttgart, this was far from a guarantee of victories. And therefore, despite the change from the Solitude from the previous year to Hockenheim for the first time for the German GP, there were still three of the extremely dangerous street circuits on the calendar, which had been reduced to just six rounds since 1956.

Respectful success in the smallest class at the start of the season and a favorite win

The reigning world champion Ubbiali (MV) set the best time with an average of 170 km/h on the 7.7 kilometer long course. His arch-rival Provini had achieved 168.9 on the FB-Mondial, followed by Colombo (MV) and Ferri on the 2-cylinder Gilera. All of this was still dry, but on Sunday morning it was raining when the field of 125s was sent out onto the track. With one annoying problem, Ferri was shut down right from the start when water got into his carburettor. As expected, there was a bitter fight between Provini and Ubbiali immediately after the start. The two fighting cocks constantly took turns in the lead. In the eleventh of 15 laps, the Mondial driver easily pulled away from his opponent on the MV, whose mechanics in the pits were gesticulating wildly that he should hurry up. But the excitement was in vain because her protégé managed to sneak up on the leader shortly before the end and was able to just overtake Provini in the last meters before the finish line.

Italian podium with surprising guests in the points

With Ubbiali’s MV works team colleague Roberto Colombo in third place and over two minutes behind his two compatriots, everyone on the podium spoke Italian. But things got interesting behind that and nobody had expected that before. It wasn’t Luigi Taveri on the third factory MV Agusta who followed in 4th place, but rather the East German Horst Fügner on his MZ two-stroke engine, who, to everyone’s surprise, was able to push the Swiss down to 5th place. Although we were a lap behind, it was still a formidable performance from Chemnitz and his team. The sensation was underlined by Ernst Degner’s 6th place with the second MZ from Zschopau, ahead of Karl Lottes on the DKW two-stroke engine. His West German compatriot Willy Scheidhauer on his private Ducati “Bialbero” missed the checkered flag, as did Sandford (Mondial) and Libanori (MV). Despite the great success of the small and modest MZ troupe from the GDR, they were expected to stay away until the final in Monza for financial and possibly political reasons. But their success was greeted with favor by the political leadership of their country behind the Iron Curtain and therefore a promise for the future.

The world champion’s second victory in the quarter-liter class

After three double victories in the first three rounds last year, everyone was excited to see whether Ubbiali would pull off this showpiece again. But Colombo with the new two-cylinder engine (Ubbiali was still driving the conventional single-cylinder engine) was also at the forefront this time. The rain had now stopped. For a long time it looked as if Provini would be able to take revenge after his narrow defeat in the 125 race. But on the thirteenth of twenty laps he overrevved his Mondial, whose engine then gave up. Colombo also had problems with a stuttering engine in the second to last round and lost contact as a result, which meant that Ubbiali safely crowned the start of the season with a double victory, as in the previous year. After Provini’s failure, Sandford made it onto the podium with the second Mondial, followed by Lorenzetti on his aging private Guzzi and only behind him was the once again luckless Taveri on the second-best factory MV. With Hallmeier in 6th place, an NSU Sportmax made it into the points this time, with Kassner, with the same production racer behind him, only missing out by one place. Behind Hartle on either a REG or private MV, there are different sources. By the way, for once the best 250cc were faster than those in the category up to 350cc.

Grand Prix of Germany up to 350 cc

On the increasingly dry track there was a dramatic decision about victory. The rain that started again made the task extremely difficult for the pilots on this high-speed route. There were a lot of falls, but fortunately they all went smoothly. One of those affected was Bob Mc Intyre on his 4-cylinder Gilera, a new addition to their factory team, at his first World Championship race. Until then, the Scot had looked like the sure winner for a long time. His teammate Liberati also slipped, but was able to quickly right his machine and continue the race, and ultimately did so brilliantly. The same applied to the German Hallmeier, who put himself in a sensational position and on the old and drilled NSU Sportmax, a production racer with an original 250cc, demonstrated its unbroken competitiveness for two years and completed the podium behind Norton specialist Hartle. Masetti in P4 ahead of Montanari, Thomson, Tostevin and the three local heroes plaintiff, Hoppe and Kauert were all already a lap behind when the checkered flag fell.

The premier class without its superstar

Defending champion John Surtees won the 500cc World Championship for MV Agusta last year with 3 wins and despite 3 failures thanks to a suspension and incredible bad luck from Geoff Duke. Instead of being able to attack again, the six-time champion (2 titles up to 350 and their 4 up to 500 cc) Duke was injured at the “Conchiglia d’Oro” (Shell Gold Cup) in Imola and had to pass. He had been the crowd-puller and superstar of the premier class for years and both the TT and the event in Assen suffered greatly from his suspension last year because significantly fewer fans made the journey to the races. Officials were to blame for this, which was explained in detail in the first part of our report on the 1956 season. In any case, Geoff Duke’s season was over again when the first race of the season started. According to his doctors, the shoulder injury from his Imola crash required a break of almost two months, after which the fast man from the Isle of Man was not expected to return to the racetrack until mid-season.

The defending champion’s bad luck in the opening race

John Surtees wasn’t lucky either when the Hockenheim race took place. Similar to the 350s, the conditions were also quite good in the premier class up to 500 cc and an improvement on Duke’s lap record from 1955 (with an average of 199.3 km/h!) was to be expected. Due to some renovation work, the course was in significantly better condition than two years before. And it wasn’t Surtees, but the Gilera factory team driver Liberati who broke the record. After the start, the 3 MV Agusta factory drivers, led by Surtees, were initially in the lead, but from the first lap Dale’s Guzzi and Mac Intyre’s Gilera were right behind. It was he who took command a little later, followed by his teammate Liberati. Behind followed Surtees ahead of Dale with the V8 Moto-Guzzi and Zeller, who had grabbed Masetti (MV). In the end, only 13 of the 28 who started reached the finish.

Prominent failures and a sensational comeback

Mc Intyre had fallen back to position 6 with engine problems and had to make a pit stop, which dropped him back to P12 and ultimately probably cost him the win. His Gilera was only running on 3 of 4 cylinders, but the mechanics were able to fix this in no time. On lap 12, the race was over for John Surtees because the rear tire on his MV gave up and the Englishman was only lucky to avoid a crash. In the meantime, the Scot Mc Intyre proved in his race to catch up that with his four-cylinder Gilera, which was again working perfectly, he could be significantly faster than Dickie Dale on the capricious V8 Moto-Guzzi. In the meantime, Guzzi newcomer Keith Campbell was out on a conventional machine (Dale was the only one on the V8). Mc Intyre, on the other hand, drove like he was unleashed and, after a new record lap with an average speed of 208.5 km/h, was now just over 20 seconds behind Liberati in P2. In the last lap it was his turn to the Italian and now, to make matters worse, it started raining again. Only because he braked in a corner was Liberati able to cross the checkered flag first with a razor-thin lead of 3 tenths. Behind them, Zeller and his two-cylinder boxer even grabbed the V8 Guzzi with Dale and crossed the finish line in third place to the cheers of the audience. MV newcomer Shepherd got the last point ahead of the private BMWs of Hiller, Riedelbauch, Hagenlocher and Huber.

50 years of the Tourist Trophy with the second round of the World Championship

In a season with, according to our quite extensive (but still probably not complete) statistics, relatively few deaths compared to the average of the first decades, the TT would have deserved not to have to complain about any deaths on its anniversary this time. The previous year there had not been a single fatal accident at the Tourist Trophy (at the TT, but not at the Manx GP on the same route), but there were two losses in Brno in 1956 (including a very prominent one with the NSU musketeer Hans Baltisberger). victims) all the worse. Unfortunately, this time there was another driver at the Tourist Trophy who didn’t survive the extremely dangerous road course. The FIM, as the highest sports authority, would watch this for decades before some stars publicly objected to fighting for world championship points here in the 1970s. Until then, it continued here year after year and the fastest pilots in history risked their necks race after race, both on the Isle of Man and on almost all other tracks. There was hardly any question of safety back then anyway, if you compare the equipment with that of 6 to 7 decades later, when airbags were even installed in racing suits.

The race in the ultra-lightweight class up to 125cc

As usual, the races of the two smaller categories and those of the sidecars took place on the Wednesday of the TT week on the much shorter Clypse Course. In contrast to the junior (up to 350cc) and senior classes of the 500cc, which each started against each other in a staggered manner on the over 60 km long Snaefell Mountain Circuit, the smaller ones were also sent on the track together. After the first lap, Taveri led Miller, but a little later Provini passed them both and took the lead. His Mondial was obviously the fastest of all the machines in the field. The reigning world champion Ubbiali, on the other hand, was unable to build on his impressive performances from the Hockenheimring. While Provini set one best time after another, the defending champion initially had no chance even against MV factory team colleague Taveri. He may have only made it past by team order and ultimately still came second ahead of the Swiss. Behind them Miller, Sandford and Colombo in last place in the points. The Czechoslovak delegation with František Bartoš on their CZ in P7, after their impressive premiere last year, missed the points this time by just one position. Nevertheless, their top driver had left numerous private MV Agusta and FB-Mondial behind. By the way, Gilera didn’t even start with their figurehead Ferri and was supposed to drop a bombshell at the end of the season.

The lightweight class of the 250cc

The 250cc race was actually the first of the day, but we prefer to keep the reporting in the usual order that would become standard decades later. The 10 laps on the “small” Clypse Course meant a distance of 175 kilometers that the riders had to complete. In cool but at least dry conditions, the mass start started on the Isle of Man. Right from the start, Sandford took the lead, with Sammy Miller (both Mondial) in his slipstream. Far behind, Provini with the Mondial, as with the 125s, is definitely the fastest. The Italian drove in his red Alfa Giulietta Sprint sports car shortly before the start and got off badly. when the start signal came. When he started chasing the lead, Ubbiali, Taveri and Colombo were behind Provini’s two leading brand colleagues on their factory MVs. He risked everything and set a new best time on lap 4 before bad luck struck him and he stopped with a defective machine. Sandford benefited from his teammate’s bad luck and won safely ahead of Taveri, Colombo and Bartoš with the surprisingly fast CZ. Ubbiali, on the other hand, like his arch-rival Provini, also did not see the checkered flag.

The junior race up to 350 cc

In the morning there was still a thick fog over the island, but it soon cleared up and clear visibility was also reported from Snaefell, the highest point on the route at around 700 meters above sea level. This meant that the start was free, which took place every 10 seconds from driver to driver, making it a race against the clock in contrast to all other Grand Prix races. For the fiftieth anniversary, as is often the case, there were ongoing announcements over the loudspeaker so that the audience could keep an overview of what was happening. A total of 77 drivers were sent onto the track, while Lomas and Duke had to miss out due to their injuries and a man with broken glasses was prevented from starting. Bob Mc Intyre only set off in seventy-ninth place, while Geoff Duke and his friend Reg Armstrong watched the action from the track. The superstar even signaled his Gilera factory teammate’s position as he drove past, who set a new best time in the first encounter.

Technical problems and falls changed the order

As the reigning world champion, MV Ass Surtees was only in P4 behind Dale (Moto-Guzzi) and Hartle (Norton) when the leader struggled with problems with his in-line four-cylinder engine, which was only running on three cylinders. After the previous leader changed candles, Dale took the lead, while Mc Intyre resumed his journey in 3rd position after his small service. A little later (on lap 3) Dale went into the pits to refuel and had to remove the casing on his Guzzi because the inspectors had discovered a crack in it. This cleared the way for Mc Intyre and the Scot drove towards a safe victory, while Dale slipped on an oil patch and shortly afterwards Dale also went off in the same place and both luckily escaped uninjured. As a result, Campbell (Guzzi) inherited second place ahead of Bob Brown (Gilera) and John Surtees (MV Agusta). About a third of those who started were canceled for various reasons. These include motor or magnet damage, chain defects and, often, broken footrests.

The premier class over its almost insane distance

It is not known what drinks the responsible FIM officials and the organizer’s employees had when they set the senior category race to 8 laps (instead of 7 in the previous year). We’re guessing that there’s a lot of hard liquor and that none of them had ever spent their lives on a racing machine with a top speed of over 260 km/h. There’s no other way you can come up with such nonsensical ideas if you’re still in your right mind. In any case, almost 500 kilometers are more in the long distance category than sprint races. And for Walter Zeller, who was initially in P3, the TT was no luck this time after finishing 4th last year. The German had to retire early due to a technical defect on his semi-factory BMW. After his victory up to 350 cc in the junior category, Mc Intyre also impressed in the seniors in the premier class and also set a historic new lap record of over 100 miles per hour for the first time. Last year’s winner Surtees came second this time on his MV, over 2 minutes behind. For the first time in three years, the top ten in the two largest categories were once again purely British and Australian, which in 1957 even applied to all classified pilots in the junior and senior classes.

The shadow over the senior race of the Tourist Trophy

Unfortunately, this time there was another fatality. Last year, the TT, but not the Manx GP, which took place on the same route, was spared from fatal accidents. At that time, the only 25-year-old Maurice William “Mog” Saluz lost his life in a fatal fall while training on the Isle of Man T.T. course behind Sulby Bridge on Friday morning, August 31, 1956. This time it was Charles F. “Charlie” Salt, already 43 years old, who did not survive the senior race. The Englishman, born on December 17, 1913 in Heanor (Derbyshire), was an experienced and thoroughbred pilot. After the war, he began racing in 1946 and was so successful that BSA hired him as a test driver from 1950 to 1956. If the Senior TT had not been held over eight rounds for the first time since its inception due to the 50th anniversary, he would have survived the race. On the last lap, Gorse Lea’s machine began to skid, presumably due to a locked gearbox. Salt hit a low stone wall and a concrete pole. He was thrown through the air and landed on the ground, trapped between a beech tree and the wall. A doctor who rushed from Ballacraine a little later found him unconscious and with various back injuries, after which he even regained consciousness and asked what had happened. He was then taken by ambulance to Nobles Hospital in Douglas, where he was given oxygen and blood. Nevertheless, he died at 3:30 p.m. Charlie’s wife and six-year-old son were in Douglas at the time, acting as his pit crew.

Unless otherwise stated, this applies to all images (© MotoGP).

No Comments Yet